Jose Barboza, a volunteer for Promise Arizona, works to get people registered to vote. (Photo by Courtney Columbus/News21)

PHOENIX — Arizona’s new law that criminalizes the collection of voters’ early ballots by volunteers could impact the ability of the elderly and Latinos to cast their votes, according to local voter outreach groups.

For the staff and volunteers who work with Latino-focused voter advocacy groups, ballot collecting is a means of outreach that accompanies voter registration, translating ballots and going door-to-door to remind people to vote. Although there is no available data on the number of ballots collected from people on the early voting list, the advocacy organizations’ staff and volunteers interviewed by Cronkite News said the new law will hinder their work and add another hurdle for voters to jump.

Cristian Avila of Mi Familia Vota said this bill “would be the biggest challenge” to his organization this year because he worries it could disenfranchise busy Latino voters for whom sitting down to fill out a ballot and mail it in may be low on their list of priorities. Avila isn’t sure what the organization’s strategy will be now that they can no longer collect ballots. He said their action plan will depend on the resources available to them at the time. They may either organize a phone bank to call Latinos on the permanent early voter list or send volunteers door-to-door to remind them to mail in their ballots.

Alicia Contreras, an employee with Promise Arizona, said the new law was already making people nervous during this year’s presidential preference election. She said people that Promise Arizona drove to the polls were afraid to let someone else in the same car turn in their ballots for them, even though the new law doesn’t take effect until the presidential election in November. Those voters walked their ballots to the polls themselves, Contreras said.

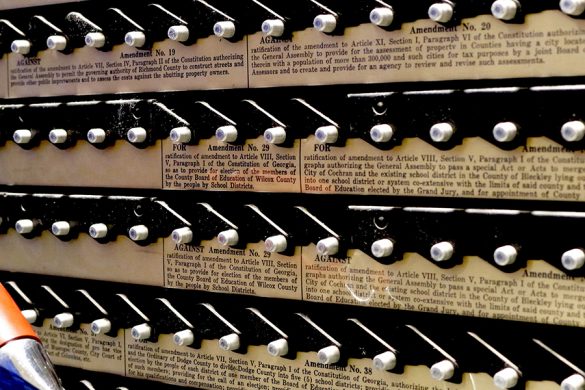

A wall at the Phoenix office of Promise Arizona depicts scenes of the importance of voting. (Photo by Courtney Columbus/News21)

She said now that ballot collection is illegal, Promise Arizona will focus on making get-out-the-vote phone calls to Latino voters and educating them about the voting process. In the past, the organization had set up car pools to help voters without transportation get to the polls.

Tory Anderson of the Arizona Alliance for Retired Americans believes that volunteers who collect ballots are also an important resource for elderly community members who may have missed the deadline to mail in their ballot or otherwise cannot make it to the polls because of a lack of transportation or because they are housebound.

Anderson said that in previous elections, the organization enlisted the help of retired members of the community to collect ballots for seniors who couldn’t make it out to the polls. She said that the law would “make felons out of retirees.”

The Alliance may consider offering rides to the polls come November now that going door-to-door to collect ballots is no longer an option.

“We just want to make sure their vote counts,” Anderson said. “We don’t care who they’re voting for.”

Gary Gilger, a Maricopa County precinct chair for the Democratic Party, said he used to collect a handful of ballots each election from voters who knew him personally and who felt it was more secure giving him their ballots than dropping them in the mail.

Legislation to curb ballot collecting, sometimes called ballot harvesting, has been in the works for at least three years in Arizona. In 2013, lawmakers passed an elections reform package that would have made it a misdemeanor. However, after enough signatures were gathered to secure a referendum in time for the 2014 midterms, legislators repealed the law.

The new law makes ballot collecting a Class 6 felony and carries a minimum prison sentence of six months. There are exceptions allowed for caregivers, nursing home staff, family members and those who live in the same household.

In Maricopa County alone, nearly 900,000 people—72 percent of eligible voters—are on the early voting list, according to information presented by county officials at a legislative hearing last month.

Ian Danley, director of One Arizona, said its member organizations, which includes Mi Familia Vota, have added between 110,000 and 125,000 Latino voters to Arizona’s early voting list since 2010. Statewide, that number represents about half of the Latino voters who have joined the list during this period, Danley said in an email. Yet, according to Census Bureau, there was in the 2012 election an 18 percent gap between Latino and white voter turnout in Arizona.

Early voting can be an alternative to going to the polls for people who often can’t take time out of the day to vote.

Araceli Vecerra, a volunteer with Living United for Change in Arizona, has voted by mail once. At LUCHA, she helps immigrants prepare for and navigate the citizenship application process that she herself completed in 2013. Speaking in Spanish, the 33-year-old housewife and mother of six said that finding time during the day to vote is often difficult for Latina women who are raising children. After voting in person once, she joined Arizona’s permanent early voting list so she could vote by mail.

Jose Barboza volunteers for Promise Arizona, another local organization that is also part of the One Arizona coalition. He helps to register voters and sign them up on the early voting list. In addition, Barboza, 24, said he collected 15 to 20 ballots at a time during the 2012 and 2014 elections and brought or mailed them to the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office.

He said that occasionally people would be suspicious of giving their ballot to him and would question what he was going to do with it. In these cases, he reassured them that their vote would be counted. “I’ve never stolen a ballot,” Barboza said.

Barboza is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who has been living in the U.S. since he was 4 years old. He said voter outreach gives him an opportunity to help new voices be heard. He echoed Avila’s belief that the new ballot harvesting law will negatively impact Promise Arizona’s efforts to get out the vote.

“It’s going to make me a felon, and I’m not a felon,” he said. “I just want to help people vote.”

A handful of other states have passed laws that curb ballot collecting. However, the Arizona law, which makes a first offense a felony, is by far the strictest. Three other states that limit ballot collection—Texas, New Jersey and Colorado—all allow a person to collect at least three ballots without facing any criminal penalties.

A 2013 Texas bill originally set out to ban the practice altogether with the intention to stop fraud. However, lawmakers and voter advocacy groups reached a compromise to reduce the scope of the bill. The final version, signed into law by then-Gov. Rick Perry, criminalizes offering compensation for ballot collecting but does not otherwise limit collection efforts.

“If you want to stop something corrupt, you go where the money is,” Sondra Haltom, the former president of Empower the Vote Texas, said. “If you make it illegal to receive payment, you get to the heart of the problem.”

Colorado allows individuals to collect a maximum of 10 ballots per person. In a recent change to New Jersey’s law, the maximum number of ballots that people may collect was reduced from 10 to three. In addition, the state requires individuals to present photo identification when dropping ballots off.

In Arizona, supporters of the law cited concerns about voter fraud.

“This legislation reforms our election laws in a way that restores the public’s respect for a process that had potentially dangerous implications and provided too much opportunity for fraud and tampering with an election,” Republican Party Chairman Robert Graham said in a press release.

But some, like University of Maryland professor Stella Rouse and legal experts from the American Civil Liberties Union and the Brennan Center, believe the ban on ballot collecting could have negative impacts. Organizations that do voter outreach often used ballot collection as a way to improve voter turnout, but they will no longer be able to do so.

“There are much less restrictive ways of preventing problems,” Wendy Weiser of the Brennan Center said of the current law.

Courtney Columbus is a Reynolds fellow. Follow her on Twitter @cmcolumbus11.