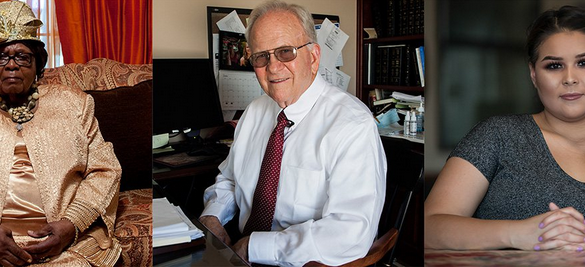

Michele Keller lost her voting rights when she was sent to prison on drug charges. Even though she was released in 2007, she hasn’t earned the right to cast a vote in an election because she hasn’t been able to pay her fines in total. (Photo by Kathryn Peifer/News21)

PHOENIX – Michele Keller has been out of prison for nearly a decade.

She was convicted three times – twice for possession of drugs and once for attempt to sell.

Since her release in 2007, Keller has worked hard to achieve most of her goals. She got a job. She bought a new car. She watched her home be built from the ground up. She hopes to graduate this year with two associate’s degrees in social work and substance abuse counseling from Pima Community College.

One thing Keller still doesn’t have: the right to vote.

Under Arizona law, one-time offenders automatically regain the right to vote after completing their sentence and paying all fines and restitution. Repeat offenders must wait two years to apply for restoration to the county court that sentenced them. They must have completed their sentence, parole and probation time and paid all fines and restitution. It’s then up to a judge to accept or deny their request.

Keller said she still needs to pay about $1,800 in fines out of $4,000 total, which she said has been a struggle.

“Survival is a first priority – housing, a job, paying bills,” she said. “Once you feel stable, then you say ‘I need to voice my opinion.’ I think that once I’ve completed parole, they should say, ‘She did good; she did well,’ that should be enough.”

Since 2013, Arizona state Sen. Martin Quezada, D-Phoenix, has proposed legislation that would restore voting rights for all ex-offenders despite the number of offenses – and without paying fines and restitution. In January, the Arizona Senate again killed the bill without giving it a hearing.

“As a community we have an obligation to help them [former felons] reintegrate into society,” Quezada said. “One way to do that is to give them the right to vote.”

But the state Sen. John Kavanagh, R-Fountain Hills, said Quezada’s bill wasn’t given a hearing because he said there should not be blanket restorations for felons of varying offenses. “They’ve shown they can’t obey the law,” he said. “It goes on a case-by-case basis. They must show they are truly reformed.”

Kavanagh added that the current requirement for former felons to pay all fines and restitution is a necessary consequence of their actions. “When the wrongs are righted, then they will be welcomed back with open arms,” he said.

Last week, Virginia’s Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe restored the right to vote to more than 200,000 Virginians who completed their sentence and parole and probation time. Earlier in February, the Maryland General Assembly restored the right to vote to nearly 40,000 ex-offenders.

Quezada said many other states are moving in this direction, which “shows that this isn’t just a crazy idea I’m having.”

“It makes sense and throughout our nation people are realizing this is something we should be doing,” he said.

Keller holds a full-time position as an instructional specialist at The University of Arizona College of Medicine. She is a single mother and receives no child support from her ex-husband.

Though her time is limited, she said other alternatives to the restoration process, such as community service, would be easier than struggling to pay.

“I think that if there was a way to do outreach and to give back that could help people who can’t afford to pay the fines,” Keller said.

But according to Quezada, the Republican majority in Arizona has little interest in alternatives. “They have been trying to suppress the vote as much as humanly possible,” he said. “They only want certain people voting.”

ACLU Arizona Executive Director Alessandra Soler Meetze said she has heard of cases where applications are denied for not paying the fines, both large and small.

Donna Leone Hamm, a retired Arizona judge and executive director of Middle Ground Prisoner Reform, said there are no classes or informational pamphlets handed out in prison to inform felons of their civil rights, such as regaining the right to vote. Middle Ground, along with the Maricopa public defender’s office, hosts a workshop four or five times a year to help former felons with the restoration process, which Hamm said is often misunderstood.

“If you asked most prisoners ‘what do you need to do to get your rights restored?’ they would have no idea,” Hamm said. “The first-time offenders we speak to here [at Middle Ground] have no idea that their rights are automatically restored.”

An ACLU Arizona 2008 survey also tested the knowledge of all 15 county election officials on Arizona laws about the restoration of voting rights to former felons.

“What we uncovered is that the vast majority of county election officials either misunderstood the law or had no basic understanding of what the process is to restoring your voting rights,” the ACLU’s Meetze said.

In a phone interview, Dianne Post, an Arizona attorney for 26 years with expertise in civil rights cases, said there are efforts being made to inform former felons of their rights. But it takes initiative by the ex-offenders to find it.

“They are told every time they’re convicted [of their rights] when they receive their sentence,” Post said. “But years later when you get out of prison nobody remembers what the hell they were told during the sentencing hearing.”

She said there are ex-offenders who want their rights back and that they shouldn’t continue to be punished. “I think many of them do want to vote,” Post said. “You break the law and you did your punishment, and when your punishment is over, you should be done.”

Post added that the reformation of rights helps integrate ex-offenders into society as a useful and worthy citizen. “When you think you’re a piece of crap and nobody cares, well then you don’t care yourself,” she said. “If you don’t care about yourself, then you don’t care what you do and you’re likely not to follow the rules.”

Some national studies have shown that voter and civic participation could curb recidivism. The Florida Parole Commission conducted a study which showed that only 11.1 percent of the nearly 31,000 individuals who had their rights restored in Florida committed new crimes.

Associate professor of sociology at the University of Minnesota, Christopher Uggen and associate director of the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University, Jeff Manza, published “Voting and Subsequent Crime and Arrest: Evidence from a Community Sample” in the Columbia Human Rights Law Review in 2004. In it, the authors state, “we might expect a relationship between political participation and recidivism for a number of reasons.”

One of those reasons is that it “facilitates the development of an identity as a productive and responsible law-abiding citizen.” The study featured a sample of 1,000 people in the Youth Development Study in Minnesota that tracked criminal behavior and voting. The study found that nearly 12 percent of the non-voters became incarcerated between 1997 and 2000, compared to less than 5 percent of voters.

In Michelle Keller’s home, photos of her 6-year-old daughter fill the white spaces on her walls.

Bible verses cover what little surface is left.

“For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord,” Keller reads one of them aloud. “Plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

Keller plans to reapply for a behavioral health position at Banner University Medical Center in Tucson, after she said she was first denied the job because of her criminal background.

“I’ve been out since 2007 and have been clean since 2005 and I’m still fighting,” Keller said, adding that she’ll continue to pay for her right to vote. “I’m a fighter. I want to fight for what’s right.”